Dan Christofferson

Dan Christofferson is an illustrator, graphic designer, and Big Cartel missionary in Salt Lake City, Utah. Dan is the nicest, most self aware guy you’ll ever meet.

Our interview took place on April 26, 2013 at his studio in downtown SLC.

What are you most passionate about?

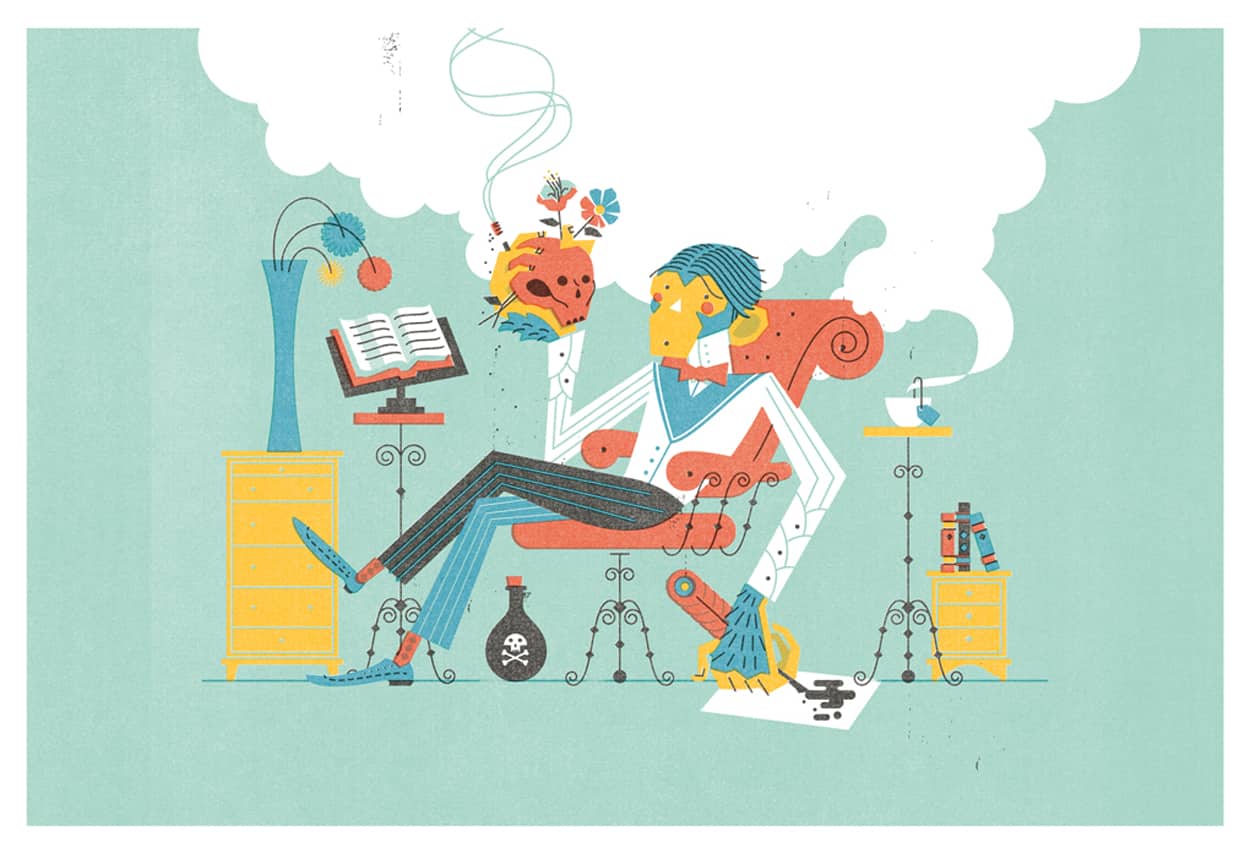

It’s that idea of all the ideas that are in my head, and all of the things that I’ve worked on cataloguing; it’s composing those into something beautiful and getting them out. I’ve never had an issue with “Where do the ideas come from?” I’ve got millions of things going on. My issue is getting them out. That’s where a lot of the late nights come from. Or not being able to sleep because there’s something I have to get out, and I’m thinking through something and I need the time and the space and the tools to get it all out onto something. That’s what is also most satisfying—that ability to turn the lights off upstairs once everything’s out. If I have an idea for a portrait of a man with a skull made of flowers and petals, and his head has the cosmos around it, then I’m pretty restless until I get it out.

So pursuing that whole idea, and living a life where I can catalogue inspiring things—which means watching a lot of movies and TV and listening to a lot of podcasts and stories, and going to a lot of museums and soaking that up, so that I build this collection of all these images, and then living a life where I do that and then being able to get it out—if I can do that at the end of the day, that’s me following my passion. That’s me living a life that’s really rewarding, whatever happens with it. The time creating and building is what’s good for me. Once it’s done, I’m sort of over it, I can kind of detach from it. But it’s that process that’s really calming. It’s actually very therapeutic. And I would imagine, though I haven’t done any research, that there’s probably something that biologically happens in artists and people that create, maybe endorphins start flowing or their blood pressure drops.

This last show I did, all of these little paintings were really small and meticulous, and I was using little brushes and sitting here so long that my shoulders were really cramped and my back was in pain, but I felt so good and so calm. Even if I was starving and hadn’t eaten and had a headache, it was sort of a way to self-medicate. I love that idea—that artists can fight the darkness or sadness by doing what they love. I’ve tried to let people know that that’s what I do and that’s how it helps me, so that I can encourage them to do that, too: Sit down and draw something, and create something, and you’ll start to feel a certain way, and then you can start to control it.

So when your head is filled with these things, and you don’t write them down, do you lose stuff?

Yeah, if I don’t write it down or I don’t sketch it even loosely, I’ll lose things sometimes. I have noticed though: I used to panic and think “This is too perfect, I need to sketch it right now.” But I realized all the good things will resurface again, and if they’re not really worth my time they will die away. Sometimes I’ll hold onto a idea, and a month later, I’ll jump back into it and realize that I forced myself to do something with it but didn’t really need to. The good stuff always resurfaces, and I think the good stuff will also force its way out. The stuff I’m really excited about, I’ll jump on right then. I’ll sit down and work it out to a point where I’m finally satisfied.

Do you play music?

I used to play drums.

That’s such a musical state of mind. I feel like a good band is able to drop ideas really quickly, or bring up the ones that seem to catch.

Yeah, when I played drums it was definitely like that. We’d try to free-form things and say “Let’s just start playing and see what comes up” and look around at each other think “What we’re doing now is cool, let’s keep this going.” We’d get to the point where we were really worried about recording it, so we could hold onto it. And then we’d say no, because if we’d come back in two days and play it again it only got better if we try to re-create it. Which goes back to something I’ve tried to work into my work ethic in art: not being satisfied at a first sketch. It feels so right to say that, but it’s really hard not to get attached to something if you like it and think “Yep! That’ll work. I can turn that into a painting.” Instead you have to force yourself to sit back and say “Alright, flip that over and redraw that same thing.” And every time I force myself to do that it gets better and better.

I think that has forced me to trust myself a lot more, to break away from planning paintings as much. I’ll take a sketch and refine it and transfer it onto a painting, and I feel like each time it could get a little looser and more organic and maybe more connected to that image I saw in my head as I let it go out. I think that creates more trust in your craft as an artist. And there’s a fear, there’s an awesome unspoken thing that happens with artists and the first page of their new sketchbook. You open it and you think “My gosh, I gotta do something cool, so I’m not gonna touch it yet.” Because there’s a lot of joy comes with creating something awesome. You’ll look at it, you’ll take a picture of it and look at it later that day, and I know a lot of artists who do that. But if you can get past that fear of creating something shitty to become a better person, I think that’s where a lot of growth happens. And those are the exercises to overcome it. You draw something, and even if you love it, draw it again. Then you start to overcome that fear, and you can start just putting pencil to paper and enjoy that process.

The most spiritual I ever feel is going to a museum or something. My heart starts beating a little faster and I start getting these ideas and it’s a recharge for the next few weeks of my life.

Was there ever a time when you were afraid about not getting a job?

Yes, but that changed. Through art school I worked collections at a call center and called people that were delinquent on their gym memberships, and I did that all day every day. I would leave class and go there for a few hours and then go back there, and at the beginning it was so horrible. I only did it because geographically it was a good location for a job. I lived here, school was here, and it was halfway in between, so I could go back and forth. I would just sit there on the phone all day, and right away I memorized everything, so I could have full conversations with people and not remember any of it, because it was just so rehearsed. And I would draw all day long; I filled notebooks and notebooks. So I realized really quickly, I don’t care what I do. If I can spend time on and put energy into the stuff that I love, I don’t necessarily care if a job deals with that, or if that is my job.

There’s a high school art class coming to the gallery next week, and I’m going to talk to them and show them sketches from the show. The art teacher said “I’m just in a panic mode because they all come to these classes and all they talk about is it’s fun but there’s no way they could ever have a job with it.” And she keeps saying “Yeah, you can! You guys can do anything you want.”

I talk with a lot of artists who scrape by, but when you see their life, it’s not scraping by, they get exactly what they want. This studio space is $300/mo, and really I could live here if I needed to, and create art all the time. I think it’s really easy to live a life like that, and just decide what you want and take it.

I also had a lot of people who encouraged me and I never questioned it, I never doubted that art is what I would do at some point. I had really supportive teachers and my parents were really good about it.

Where’d you grow up?

Here in Salt Lake. West Valley and Davis County. But even as a little kid I knew that I would do this somehow. I think the big change came for me after my first year in art school where I originally was in painting and drawing, and it was very focused on oil painting and fine art. Everybody that I was working with was like “Cool, so when you’re done here, where do you want to teach?” Which was just the assumption–if your’e fine artist, you obviously just teach fine art to make a living. And I never thought that. I never wanted to do that, so I sort of panicked a little bit at that point and thought “What do you mean? I don’t want to teach, I want to create cool shit.”

So, across the hall from the painting and drawing department was where the commercial artists were, the graphic designers and illustrators who were focusing on commercial illustration, and I saw a lot of things that I was already doing. I was trying to include typography in some of my paintings, and my paintings were very graphic and I was trying to simplify shapes. I saw that across the hall and thought, well I can mix all of this stuff. I thought, I can use oil paints in commercial illustration work. So I jumped ship and went over to that side of it. At Weber State it was a VSCOM—visual communications degree, and then you could emphasize in either graphic design or illustration. So I moved over there and focused on illustration but I still took painting and figure drawing classes and used my ability to render and paint over there, and it all seemed to make a lot of sense after that. I could call it this, and I could learn these skills of typography and layout, and maybe some of the business skills of the commercial side of art, but use the same skills and talents that I was developing over there.

Is art your hobby, or is Big Cartel your hobby?

The connection with Big Cartel is a really beautiful thing that happened at the perfect time in my life. I was working full-time doing design, mixed in with a lot of illustration, and I was to the point where I thought I could jump out on my own and start doing just freelance. But I was worried about the business side of it. I was worried about what it would turn into and what my brand would become.

Deep in my heart I’m an artist, and one of the things that I love about artists is that we’re sort of flaky, and we’re all over the place and we’re not the most organized business professionals. So I was really worried about that and some of the aspects of marketing and how do I make it all feel right, and how do I market myself.

I was explaining these fears to my buddy who runs Big cartel, and I said “I don’t know what I’m going to do.” I’d always been very charismatic about the product of Big Cartel, because I had my own store, and sold my own prints and T-shirts. To everyone I came into contact with I would say “Oh, are you selling stuff online? They built this really cool tool, and you can set up a store really easily.” I identified myself as a user, as an artist using this thing and making sort of a living off of selling prints and stuff. And even when I didn’t put in the work to sell a lot, I could see a clear way where any artist could make some money off of their craft.

So I was explaining my fears to my friend and he said “Well, we are to the point where we need somebody to help preach what they’re practicing.” It was a perfect time for me to jump in and help start telling the story: “Hey, everyone out there, you can make a living being an artist. You can make a living doing creative things. There’s people who love the idea of, and are blown away by a creative person who makes something out of nothing.” Which I think is what the definition of an artist is: I have this idea, and I’ll make it all happen. I’ll build a canvas, I’ll stretch it and gesso it. And there’s people who will support that. A service like Big Cartel is priceless in this modern era of simple tools that help artists promote themselves.

So, it all actually worked so seamlessly, it’s hard for me to define. Everything I learn on my own, from my own brand or my own art shows, I can use over at Big Cartel. And anything that works over there, I use in my own studio work and gallery shows. Since I’m just sort of following my passions, I don’t necessarily have a schedule, I just sort of mix it all. To me, that’s been the most successful way to do it: to help champion a cause that I’m actually living and promoting personally.

That changes it from a 9 to 5 job you have so you can work on your art at night, to 12+ hours a day that you’re doing what you love.

Yeah, it is, and that’s maybe the sacrifice, but also the reward. It’s hard to call it a sacrifice, but the reward is that when you find that thing, you do it all the time, and rather than saying “I do this so I can do this,” you have to train the people around you: “Yes I’m always working, but I’m always doing what I love.” It’s essentially—I sort of love this idea—if you built something, sold it, and had money to do anything you wanted, I’m doing that right now. If I had millions and millions of dollars, this is what I’d be doing every day, all day. And I think that’s more easy to find for people than we think.

People have a really hard time with it, especially people who are focused on “Well what’s your job? How do you make money?” And you start to realize “Oh, you have a certain idea of what you want to make. You have a dollar figure. It doesn’t relate to anything in your life, it doesn’t relate to what you’re going to do with that dollar figure, you just have that number and you’re trying to work away into that.” And I don’t necessarily agree with that way of thinking. If you create a way where you’re doing what you love all day, the good stuff will follow. The money to support it, the awesomeness, the success will follow.

I work next to a couple of government buildings, and if you walk outside at 5:01 it’s unbelievable. Every car is streaming out. And to me, it’s really amazing because they’re driving away and the night’s theirs—they can do anything they want. But they hate their job, I assume, because why would you leave exactly at five?

What have you had to sacrifice to do what you love?

I think that’s part of what I was talking about earlier. Every once in a while I’ll have this fantasy of a normal day job, like working retail—I love people, so I’d love shaking hands, and I would love restocking a shelf. And then you’d go home at five o’clock, and you’re done. You’re not thinking about it, you’re not consumed by it, and it’s not affecting your conversations. With me, everything is always cooking, so when I try and sit down with the people I love—my girlfriend, and we’re having an honest conversation, I’m so distracted, and I’m just fighting to stay with her. Whether it’s something very important, or just her day. Because I’ve trained my mind so that I’m always on, because anything could be inspiring to some cool story and trigger whatever. So I lose a lot of that ability to shut it off, which I think is very comforting for humans: to be able to shut it off, sit down, and just focus on something else. I can compartmentalize to some extent, but I’ve sacrificed some of that normalcy.

I fantasize about it every once in a while, that 9 to 5 job. I work next to a couple of government buildings, and if you walk outside at 5:01 it’s unbelievable. Every car is streaming out. And to me, it’s really amazing because they’re driving away and the night’s theirs—they can do anything they want. But they hate their job, I assume, because why would you leave exactly at 5? They’re told they have to work until a certain point and then they’re done. But you don’t think about that stuff if you love your job or if you love what you’re doing. So it’s hard to say it’s a sacrifice, but that’s what I miss out on in order to have something where all night long, all day long I’m involved in something that I love doing.

Do you get stressed when you’re not “getting it out” and focusing on what you love?

Absolutely. I have to do it. I worked for 3 months straight on this last show; any time I had free away from emails or the computer or digital illustrations, I would come here and paint. When you’re painting, you’re just consumed, you’re focused. So I would paint all the time, and that was an amazing feeling and gave me this sort of high, and then the day the show went up, I didn’t have any paintings in the works. So for the last few days I’ve been stir-crazy, and I’ve been creating ideas, but it’s been really hard, and people that are close to me are saying “Hey, you should probably figure out a studio night soon because you’re getting sort of crabby,” or something like that. So it’s gotten to where I’ll notice it really quickly. The day after my show was a Saturday and I planned it to be a relaxing day, and I couldn’t just sit there and not do anything, I had to start sketching. Which was really cool to me, to see that no part of it felt like “Oh good, I’m done.” Every part of it felt like “Yay, I got to do all that, and I’ll do it again today.”

That’s really nice.

Yeah! It’s really cool and it’s really rewarding to talk with other people that feel like that and to pass that on. I get this excitement out, and I talked to people who came to the show and have been inspired to create on their own. I do the same thing. The most spiritual I ever feel is going to a museum or something. My heart starts beating a little faster and I start getting these ideas and it’s a recharge for the next few weeks of my life.

One last question: If you had to sum up advice for other creatives in one word, what would it be?

I guess for me it would be “Hands.” From early on I realized the most expressive things you could ever draw are faces and hands, and I have always been really interested in hands and what people do with them and what that means and how to tell a story. It’s sort of like a second face—if you look at their face and they’re saying something, you’ve got to look at their hands and see if it’s backing it up or not. It tells a story, and you’ll see when I start thinking I start wringing them or popping knuckles. And also because it deals with work: everything comes through your hands when you’re creating work.