John Hendrix

John Hendrix is a passionate illustrator, and a kind soul. The answers from his interview gave us a small taste of what quick wisdom his students at Washington University get all the time.

Our interview took place on at his home studio in St Louis.

I’ve always wondered about artists who work from their house, and especially since you have kids: when are they allowed to come in to your studio?

I have big rules, but they always dissolve immediately. I do keep candy in here, so they know when they come down they get something fun. My kids are totally welcome, and they paint and hang out down here sometimes. I have an eight-year-old son and a four-year-old daughter. They get what I do, to a point. Though, at one point my son thought I made all of the picture books in the world. He came home and said “Dad, we read your picture book at school today.” I said, “Oh, that’s great! Which one?” And he said The Polar Express. And I said “I wish.”

But he gets that I make art and that’s my job, and I think that’s cool. I try to encourage it in him as much as possible, but my dad was super cool with encouraging me, but not forcing me to do things, so I’m trying not to be like "We’re gonna take art lessons and you’re gonna be the next whatever." I just want to make sure he does what he’s interested in.

I’m really lucky that my job is so connected to something that I love. I try to remember that love on days when I’m frustrated or I’m doing stuff that I don’t think is as good as I want it to be, because I still am one of the small percentage of humankind that gets to do the thing that they’re most passionate about.

That’s a phenomenal thing for a parent to realize.

Everyone we know is having a baby right now, and it’s easy for us to have lofty ideas about parenting when we don’t have a baby. But you actually have kids, and you’re still saying an ideal thing.

I think you should absolutely go into parenting with a lot of ideals, because those are the ideas that get eroded eventually, so then you’ll have a nice baseline of ideals—it’s messy; the way it should be. I have friends who are artists and have dedicated their life to their work, and say they’re not ready for kids, and I really understand that. I really understand the feeling that you’re going to lose your work, which is an incredibly important expression of who you are.

But there was a moment a couple weeks ago when I was with my family, and I just felt like: "This is the best thing I’m ever gonna make. I’m never gonna beat this." I feel sorrow for my friends that don’t want that. I know what a huge sacrifice it is to have family, but I just think when you’re old, when all your friends are old and all your other family is dead, you’re going to have a family that’s yours. I mean, that’s a pretty macabre way to see family, but I don’t know.

How has having kids been a sacrifice for your art?

I think if I was alone, if I was just me being a Bohemian artist, I don’t know if I would live in St. Louis. I would probably live in New York with other “creatives.” I would probably dedicate every moment of my waking life to making art and making things that cemented my place in visual culture. On some level, that’s incredibly poisonous.

How so?

I think raw, unchecked ambition can be detrimental to self. In some ways, family has offered a check against that for me… because work is certainly good because there’s so much to it that’s excellent and amazing. But family, and even teaching, to some degree, are ways to push back against the selfish drive of making things that are for yourself and the enjoyment of making work and all that.

Before you had kids, were you doing art all the time?

Yeah, when I lived in New York City for four years, it was like art camp. My wife and I were married, but our lives were completely centered around my work and what I did and the friends I met there. And it was amazing. It was intoxicating. New York is like a chapel of work. Everyone is so dedicated to their work that it doesn’t seem bizarre to work constantly, all the time. I remember when—I still actually struggle with this—going to bed seemed a little bit like a failure. The feeling was, every moment that I can be awake, I need to be working. There are still nights I’ll go to bed at like 12:30 am and feel like “Oh, gosh, I’m not really committed.”

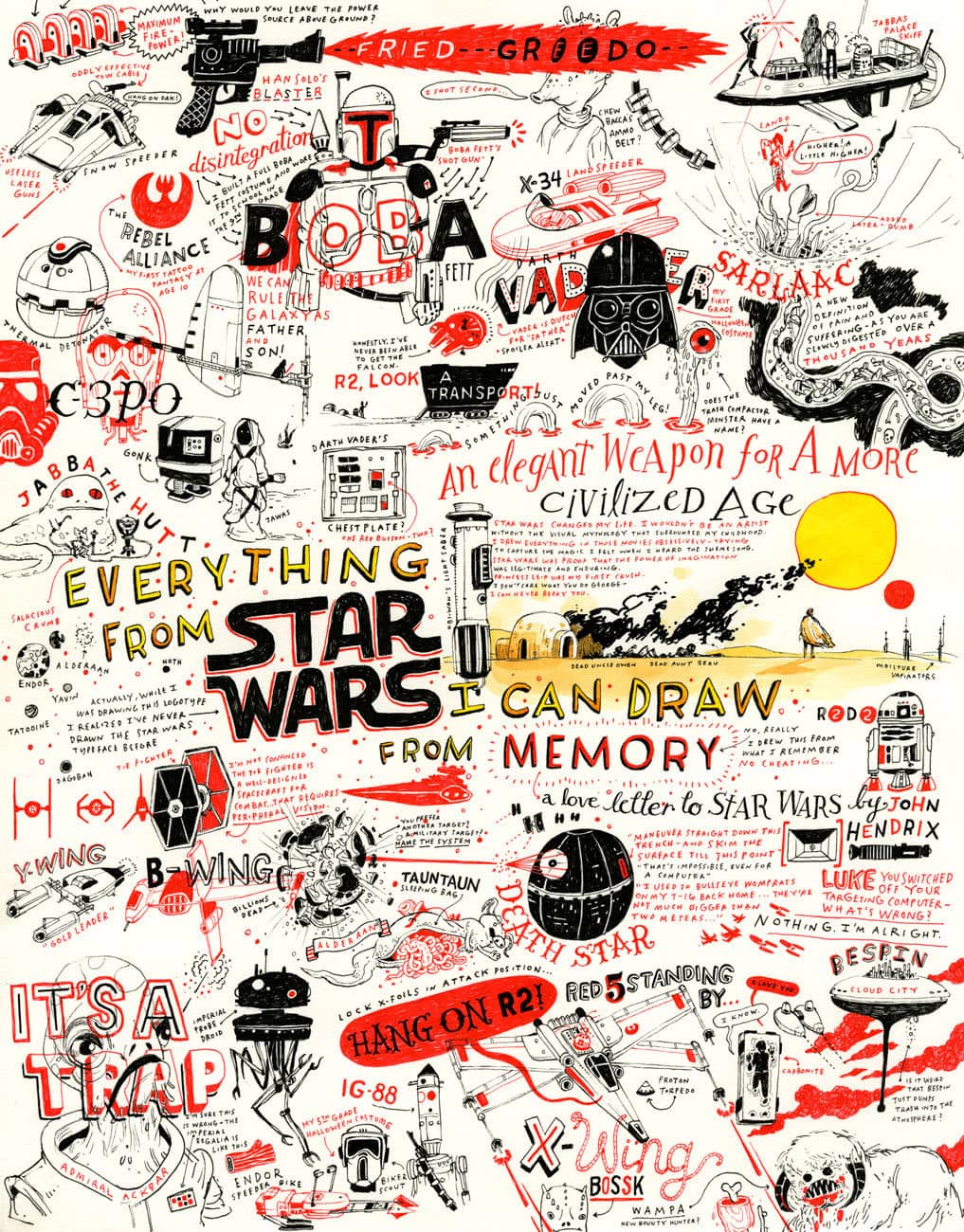

What are you most passionate about?

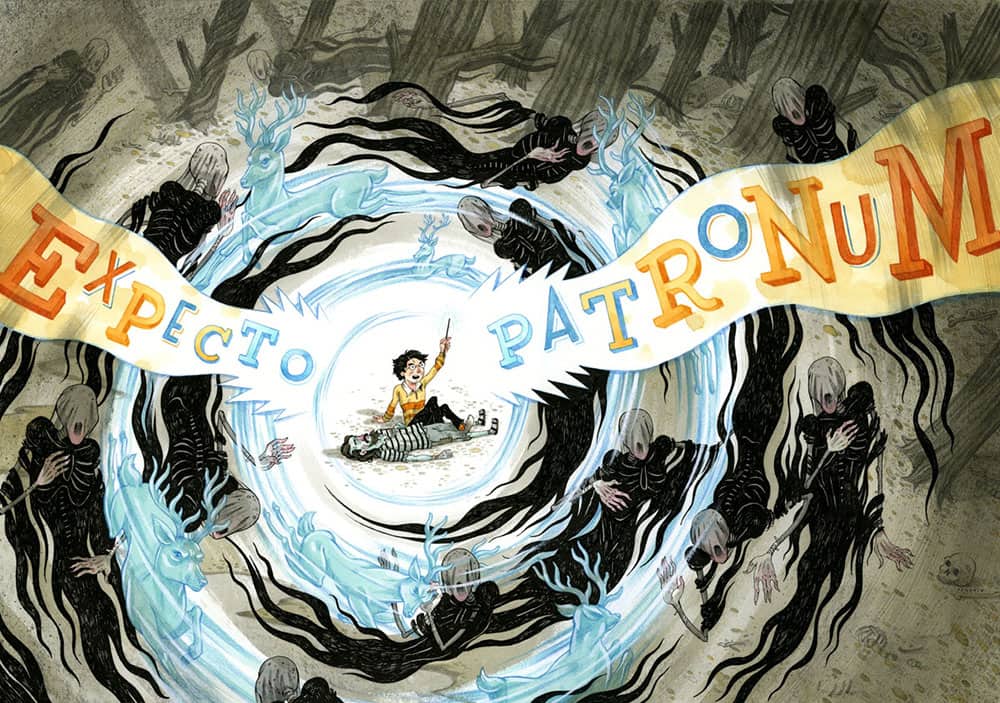

I’m passionate about drawing, making images, storytelling. When I think about the stuff that was important to me when I formed the idea of loving drawing, it was always centered around storytelling and making magical pictures and images that opened up new worlds and new things I’d never seen before. All of my work is about drawing and the love of drawing—how drawing is just an elemental thing in my life. I’m really lucky that my job is so connected to something that I love. I try to remember that love on days when I’m frustrated or I’m doing stuff that I don’t think is as good as I want it to be, because I still am one of the small percentage of humankind that gets to do the thing that they’re most passionate about.

When you worked at design firms, did you feel that you were doing what you love?

No! And that’s what was so crushing. I got out of school and I had all these ideas about what design is and process. I still remember I was given a logo to do for an online bank, and I worked all night on these logo sketches and brought in like fifteen sketches. And at the big meeting with my creative director and everyone, I showed fifteen sketches and was talking about what the concept was, and super excited about my process, and he just said: “They’re great, but next time, don’t even do the sketch, just do the logo. You gotta get to the next project, it’s not worth all that." And immediately, I thought "My professors lied to me! The process is a sham!”

So I was really disillusioned my first couple jobs. My first job was in PR and it was really corporate. My second job was a lot better, it was in a small boutique design firm, but I was still designing and art directing, and not drawing every day. I got to do some posters where I could draw, but I got to that spot where I realized “This is going to be the rest of my life” because I was making a paycheck and not starving and had a good job. So that’s when I decided to take out sixty grand worth of loans and go to New York, because I needed to put something on the line.

Were you married when you took out those loans? How hard was it to make that decision?

I remember really regretting being married at the time—not because I didn’t like my wife. I just had so many friends who seemed like they were enjoying their twenties, and I was working this terrible job, nine to six every day. And I got that job because I thought “Oh I’m married, I need to have a job, that’s what you do.” So it really pushed me into a career that I was angry about. But that choice was so good for me, looking back. I learned a ton of stuff. I later went on to work at the NY Times, and I never would have gotten that job if I hadn’t worked in corporate PR for a couple years, where I knew how to deliver bad news on the phone, and how to talk to a boss, and be professional in a context where you can’t just email people. So that time turned out to be really useful. I never would have chosen that, is sort of my point.

So being married and saying: I’m making money, but do we want leave this and go to graduate school? Do we want to take out these loans? Do we want to give up a job? My wife Andrea was so great. She had a really great job, really a dream job for her. She was working at a campus ministry—she didn’t study theology, has no seminary degree—but got a job ministering to women, and essentially hung out with people all day. And, we had to get rid of our dog to move to New York. So it was all these sacrifices that she made directly for us to go.

And she denies this, but she’s the one who told me to go back to grad school. She doesn’t remember this conversation, but I vividly remember being completely despondent on my bed, just saying “What am I doing?” And I remember her saying “We should go back to school. Why don’t we do something?” I just remember it so vividly, and she denies that it ever happened, but I remember thinking “Yeah, why don’t we just move to New York?”

After that, we went on our first visit to New York, to just see the school and look at where would we live, and Andrea, she cried the whole time. In the hotel room, she said “I can’t do this, I don’t know what this is.” She cried on the plane on the way out and said “I’m scared of this place.” I mean, it was truly a disaster. We were staying in the Upper West Side in this Best Western that was the size of this table; it was so tiny. She would not leave the hotel room. She said “I’m afraid I’m gonna get lost, I’m afraid it’s not safe.”

Where is she from?

St. Louis—we’re both from here. So we were Midwestern hicks, essentially, coming to the big city thinking that every person is a murderer. So the first trip was not good, but God bless her, she came. And it ended up being an incredibly formative experience in our marriage and in my career. It was a great adventure, but in some ways, it was a sacrifice too. We’re still sort of chained to that debt. In that time we didn’t travel a lot—essentially our travel and adventure was just living in New York. Which was amazing, but we didn’t have a lot of the early adventures you could have as young people when you don’t need to make a lot of money, and you don’t need to have a lot of overhead income to live. 1800 dollars of rent is a real burden. You’ve got to work to pay that off, and there’s this sense that New York is going to eat you if you don’t keep making money.

How worth it did it feel then, and how worth it does it feel now?

I’m a very optimistic person by nature. I tend to be a sort of magical thinker. When I was there, I was like “This is all going to work out.” And only since leaving do I look back and realize “What in the world, how risky was that!” But at the time I thought “This is amazing, I’ve totally got this. I’m totally going to move to New York City and become an illustrator.” That seemed a very reasonable assumption. I look back on it now and think that’s crazy.

But I think a lot of artists have that weird sense of going between thinking they’re a genius and a hack, over and over again. And there’s also this magical sense of “It’s going to work. I’m going to make it work because I can totally do that.” I have an amazing ability to put aside failures that I’ve had—I think it’s survival. I don’t think it’s because I’m this rigorous thinker. It’s because I can’t dwell on the failures. I just can’t keep making things if I think about the bad stuff I’ve made over and over again.

Just yesterday, I was scrolling through something on my computer and I found a piece I hadn’t seen in years and it actually caused me to let out an audible groan. I involuntarily went "Uhhhh." I was just overwhelmed thinking “Is this what I was making then?" Obviously I push that stuff away and I think of my best work, because I have to. I have to think of the best stuff I made; otherwise, I can’t keep making things.

Besides the things you’ve already mentioned, what have you had to sacrifice to pursue your passion?

Even in teaching, I think there’s a level of sacrifice, because you take time out from your own work. You get a ton back, I think, from students, when you’re interacting with them, when you’re trying to help them become the sort of people they want to be. I try and remember that on those days I feel totally down and am thinking I’m giving too much time to other people and not enough time to my work. Or fearing I’m not really as committed as people who still live in New York and can dedicate huge chunks of their life to making their stuff.

That’s why we did this project. I feel like everyone says "to be successful, you have to be obsessed." So when you feel that you’re not obsessing enough, how do you deal with it?

I do think that there is a level of obsession that is needed to make work like this. It’s actually sort of insane when you think that you can spend a week making an image that someone can consume in less than a second. Right?! That’s not good math. It makes me think of the poor graphic novelists—I read Amulet by Kazu to my son the other day and I read it to him in maybe an hour. And that was maybe a year’s worth of work. It’s not fair at all.

So there has to be a level of obsession, I think, to make art continually. And I don’t think that’s always a bad thing. I say that, though, and I also fear the obsession, too. I fear art controlling too much of my life, and controlling too much of my mental fabric. When I continually think about the work even when I leave the studio—that’s one of the things I’ve really tried to work on, as my kids have gotten older. At the end of the day, I want to go upstairs and leave that all behind. For example, that terrible drawing of that guy I made; I’m going to leave it downstairs.

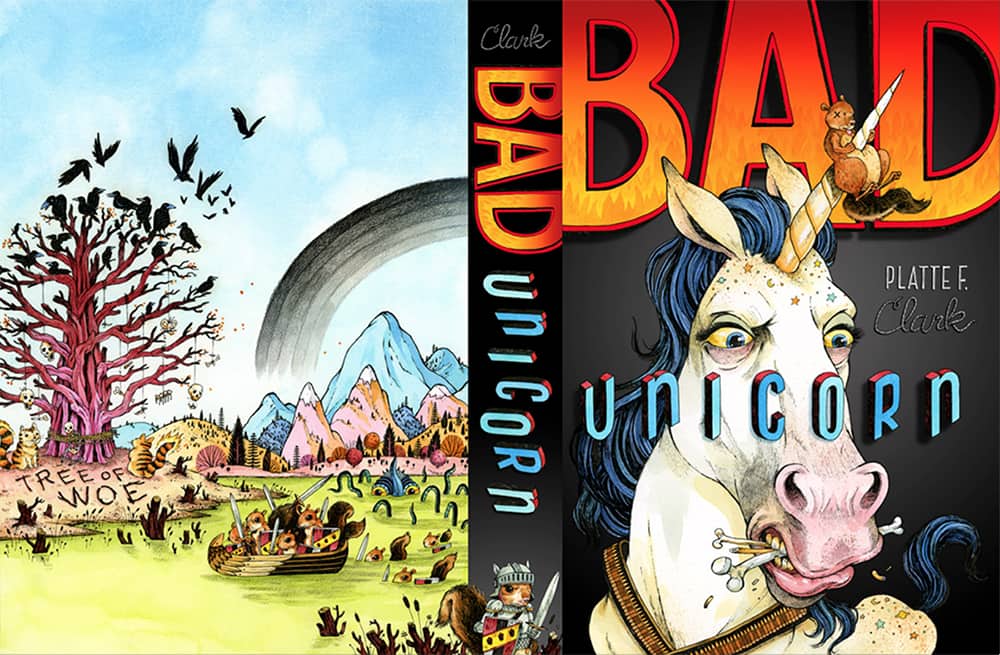

[...] I’ve been going more towards the books as I get older, mainly because I think I do crave a sense of permanence, or of a catalogue of work, or of something that feels significant.

What are you afraid you’ll never accomplish?

Oh man, [laughs] I don’t know. I’ve talked with Sam Weber about this a lot: the whole idea of “What is it that we’re making? What are we leaving behind? What is the goal here?” I’ve always said I want to make a lasting work of staggering genius that the world has never seen. I mean, honestly, that’s what I think! It’s insane to even say it out loud, but I think that. "Is it possible that I could make some dumb thing that could stand the test of time throughout the history of the world?" I don’t know. That can’t be what I’m going for, but I actually think it might be.

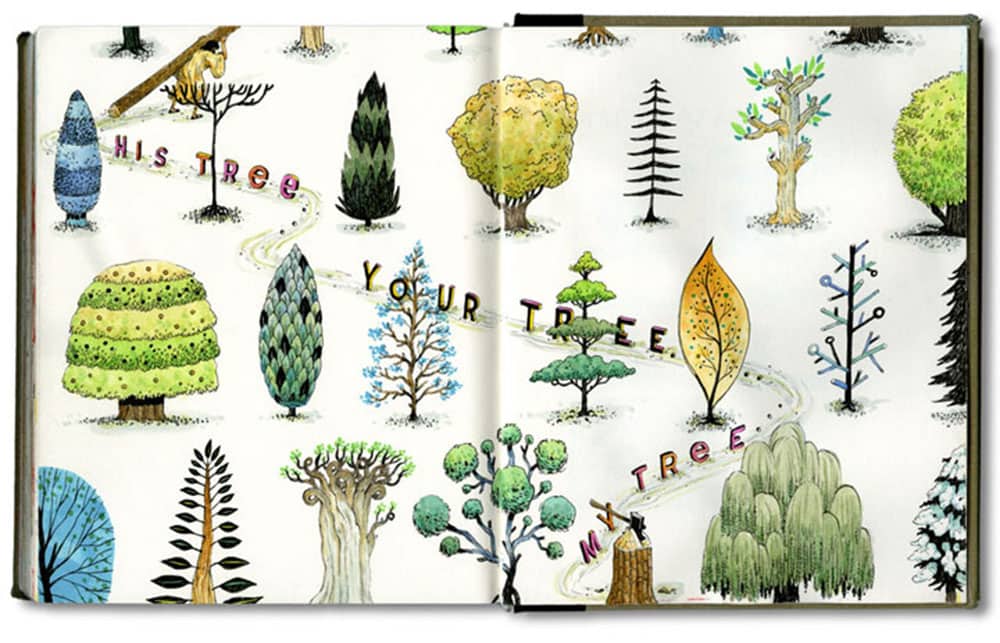

So, there’s a level of insanity as well. I guess I want to enjoy what I’m making; I want to wake up every day, and love drawing and love the experience of seeing it when it’s done. But I guess I want to make stuff that lasts? What’s the definition of “lasts” though? That’s why I’ve moved from editorial into kids’ books. The thing I make in a magazine is on the stand for a week, and then it goes in the kitty litter tray. At least the book goes on a shelf and it lives in a library for a while, and kids experience it and they read it, and I get letters from kids, and that feels amazing. So, I’ve been going more towards the books as I get older, mainly because I think I do crave a sense of permanence, or of a catalogue of work, or of something that feels significant.

Right now, today, do you feel like the work you’re doing is completely what you love?

I do feel like I still have a level to get to. And I don’t know if that’s something I invent in order to keep myself working. It does seem crazy. I’m doing exactly what I want: I’m writing my own books, and designing projects that I have written and authored, and I’m selling them to people and they’re getting published. There is nothing else that you can do, as far as I know. And yet! There is more that I want to do.

It’s just different kinds of projects, or projects that reach a bigger audience—that’s important to me now. Not just writing a book and having it published, but writing a book and having it well-reviewed and popular, to sell well, to find your audience out there. So yeah, there are tons of things that I still want to do. Just yesterday, I tweeted that I wanted the world to ignore all the previous images I’d ever made because I feel like I just figured it out. Ten years in, and I still feel like I think I’m just about to figure out how to make something. So it feels like that now. I’ve written several books, but I feel like I’m just getting my sea legs.

Where do you think you get that insatiability? When you look inside where does it come from?

That’s such a good question. I don’t know if you can teach desire or not. I don’t believe in talent, really—I think there are gifts that people have, but I think that 90% of what people do in their career is hard work, and then there’s that x-factor of "Do you want to do it, do you love it, are you passionate about it?" I think some of it had to come from my family and my parents who were supportive and who always thought what I did was interesting and were big fans of my work.

And it’s not exactly practical. Sometimes it’s a desire to make things that make no sense. Or it’s a desire to make stuff that is unmarketable, that you’re not getting paid for. Like today, I spent two hours working on a t-shirt of a comic character I’m working on that has no function! It has no purpose. I’m not going to make the shirts, I’m not going to do anything with it, but for whatever reason, I had to work on it. And some of that is bad time management, but sometimes it is knowing that you sort of have to follow the things that you’re interested in, even when that is unpractical.

If you could pick just one word that’s your best advice to “creatives,” what is it?

“Patience.” I thought long and hard about this, and I kept coming back to it. I wanted a better word, but it was the first word that came to mind. I wanted something like “Passion!” or “Desire!” But I just wish somebody had said to me in school: “Relax. You don’t have to come out of school and be the Caldecott winner.” The great thing about drawing and making art and design and type is that you can do it your whole life.

I just heard this amazing interview with Gregory Manchess, and he’s in his fifties, and he said, actually, a very similar thing to what I said before: “I think I finally figured out how to make something.” So you can go your whole life and keep learning and getting better, and I certainly came out of school just incredibly anxious about succeeding or getting in annuals, or having some awards that prove I’m going up, not down. And it ended up being a kind of obsession that was not helpful. It was not an obsession where you’re passionate and you love creating; it was an obsession that was a spiral of just navel-gazing.

So I try to tell my students, just relax. If you make stuff that you are interested in and you think is valuable, ultimately an audience will find you if that stuff is good and well-made and interesting. The one comfort you can take from illustration is that it’s almost a pure meritocracy, in that the good work, I think, will get seen if it’s good. So set your mind to making stuff that’s excellent, that’s good, true, and beautiful. I think if you do that over and over, people will find your work.

Note: Original interview content has been modified for length and focus. See full interview here.