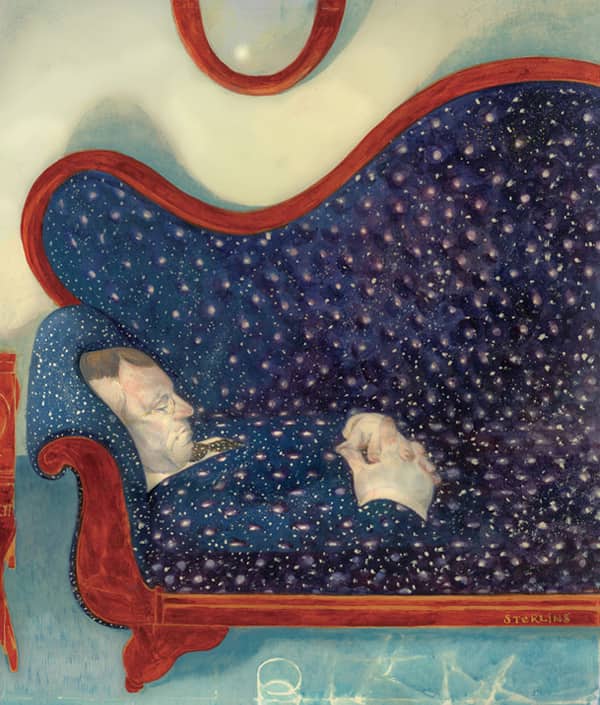

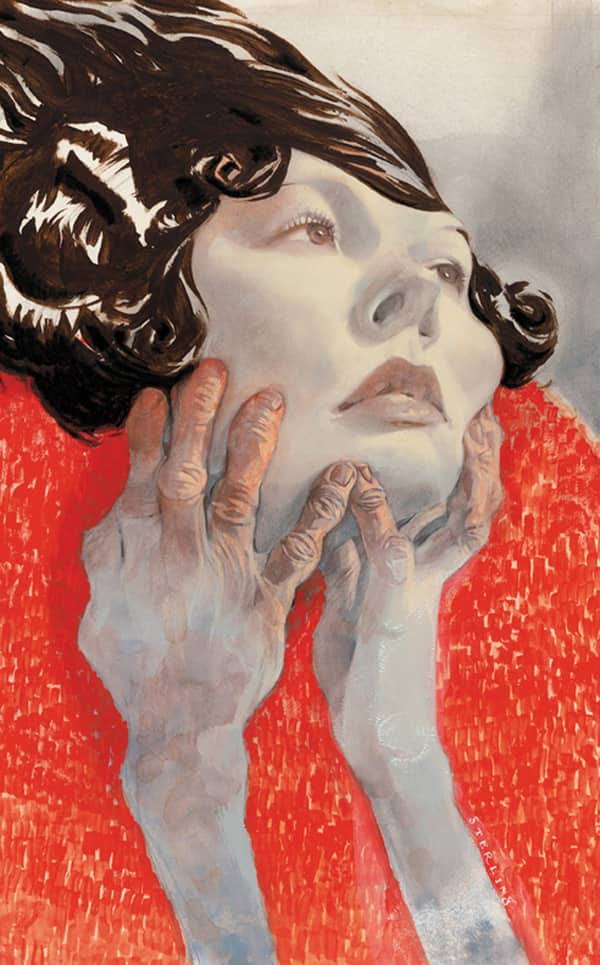

Sterling Hundley

Sterling Hundley is a painter, illustrator, and teacher at The Art Department.

Our interview took place on on the loft at The Art Department.

What are some of those things you’re afraid of never accomplishing?

Anything, right now [laughs]. This ambition of mine to be a painter and to move away from commercial illustration; I just haven't been able to focus on it because of other responsibilities. So, I'm just going to be tired.

It'll be that way for a while, and then I'll have a body of work, and then I'll get to sell that body of work. I actually enjoy that part: meeting people, and making connections. When I was an illustrator, I'd take these trips up to New York for promotion, even though people always told me not to do that: "You'll never get appointments with art directors, they'll never have time for you." When I got up there, I did everything I could to meet with people face to face and hopefully leave a lasting impression.

As I teach and think about my own fears of taking my new body of work up to New York and starting over and getting smacked around and going through all of those things again, I get propelled and compelled by the fact that I'm afraid of it. I want to face those fears. If you realize that those are opportunities for momentum, that most people in the world don't live their life [facing their fears], that they're going to shy away from things that are impediments….[well] I see them as opportunities. If you can approach things like that, you find yourself in a playing field where no one else is.

We have a student right now from the career mentor program, and her name is Aly Hodges (http://allyhodges.com/), and she is dogged in her determination. She's amazingly intriguing to me in the sense that she is inherently shy—Aly, I hope you don't mind me talking about you like this [laughs]—but her natural instinct is to be shy. But she's so determined and fixated on doing this that she's up in New York right now, by herself, up there promoting her wares and trying to meet with art directors. It's hugely inspiring to me when people overcome their nature and go and do things like that.

Fear motivates me. When I was a kid, I was climbing radio towers because I was afraid of heights. I had pet snakes because I was terrified of snakes. I run at hills, that's what I tell people. I used to run cross country and play basketball. My mentality was: people would take it easy on hills, they'd want to run down hills, but they'd get to a hill and coast and run slow. I like to think I run at hills.

What does it take in order for you to feel satisfied at the end of each day?

Progress, I guess, is what I'm looking for each day. Most days it doesn't happen, right now. My daily goals are just to get things accomplished. I guess if I had a goal as a teacher [it would be to] connect with a student and get them to light up. You'll say things fifteen different ways, and you'll get a [confused] look, and then all of a sudden you'll see it click for them, and you'll know you got through, because they can recite it back and they own that information now.

As a director of the school, if we can come down here and have a great day in the studio where people are productive, and people are helping each other and doing something ambitious, that's a great day here. As a painter, [to] walk away from the canvas—if I get to a canvas [laughs]—and leave on a high note is pretty good. I left on a high note painting last night. I was up until 3:00 am, back in here at 10:00 this morning, dropped my daughter off at school at 9:30 [in the morning]. I'll be up probably just as late tonight, so that's just what it is. The catalogue [from my kickstarter] I showed you before: I was pleased with some of the paintings in the show. I was pleased with the design. I was pleased with the cover. The moment that we embossed the cover with silver ink, and it was done—that was satisfying. That was the most satisfying thing of the entire creative process for the kickstarter campaign, the exhibition or anything else. Wrap it up, done, and I loved it. That's what you live for.

How long does that feeling last?

[laughs] I can still look at [the catalogues] and I don't want to send them out because I like them so much. I want to keep all hundred copies for myself! I would say [the feeling] lasts until you begin to question what you've done. I guess I would summarize it by saying, I don't vacation well. I don't weekend well, which means that I can't sit still. I'm fidgety, and I'm always moving, and I think I'm like a shark. Once I'm sitting still, I'm asleep.

It doesn't last very long, and the truth is, I've got an entire philosophy behind how to shorten the length of time that it takes to discover personal voice. That's what I teach at the career mentor program, and it's scalable from fashion design, to illustration, to painting, to writing, to dance, whatever. Whatever requires a personal distinction and personal voice. The process is identifying first, what you love and what you loathe, so you go through an intensive writing process. Go back to the roots of why you made artwork in the first place. Did you make it for yourself? If that's the case, then that's therapy. You've got something inside you that you're trying to get out. And if it stopped at that, then that's all it would ever be, therapy.

It's not until you choose to share it with another person and that person connects with the thing you made—it could be incredibly nuanced and specific, but because it's part of the tapestry of the larger human story, experience, condition, and everything's cyclical, you're going to connect with other people and say, "You know, that song, those lyrics were written about me. That painting resonates with me." Figuring out how to interject your own thoughts and your own ambitions and use that as a fuel to motivate you forward is the first step, and then you really have to figure out what things you're trying to bring together, and it becomes a hypothesis. If you can figure out, through experimentation, through the labor of making things, the dialogue of making artwork, you will arrive at that solution eventually. And once [I've] arrived at it, that's when I get bored. Because I've done it. I've figured it out. You get excited for a moment, because you figured it out, and then you say "What's next?" I think that's probably where I'm struggling right now. What is the fixation point that I'm trying to accomplish? I've got almost too many things that I'm trying to converge together, but there's something there. I'm going to figure it out.

What are you most passionate about?

Hmmm...story.

As an illustrator, you're always relegated to someone else's story: here's a manuscript, here's a text, here's something to react to. As a painter, there's a distinction. [In painting or high art] narrative is often frowned upon. In many people's opinion, it cheapens the thing that you're making, because it's too accessible: "Well, if I can understand your story, then it's too easy. It must not be high art." The thinking is kind of backwards on it.

So, paintings have become convoluted, fine art has become very watered down, and there's this premise that [painting is] all about the artist, and I hate that idea because without an audience, art serves no function. If things are so obtuse and aloof that they prohibit the viewer from accessing the intent—and from the intent that's where we get content—then what's the point?

I do believe that paintings should be open-ended, much more so than illustration. You have limitations of time and space in illustration: time with the viewer, and space in which to show it. And in painting, you have galleries and museums, and these cavernous spaces that are dedicated to appreciating the artwork. And people go there on their leisure time. So they have plenty of time to consider and think, and if someone buys a painting they take it and put it on their wall in their home or place of business, and if it reveals itself too quickly, then it's too easy. It should avail itself over time.

A lot of those things have been motivators for me pushing away from the commercial world and to finding my own voice and having autonomy for what I do. That said, success can be its own trap. And if you start selling at a gallery and there are certain things that you're doing that sell, don't think that it doesn't become the most commercial thing in the world. The gallery owner has money they have to pay out for their electricity bill and their gallery space and everything else, and they want to sell paintings. And as much as they might like you as a person or believe in your writing, if you're not selling paintings, then you don't have much value to them. And they expect you to continue to do that.

So, I like that illustration has been a great place for me to go through the motions of articulating concept, practicing with material, and because the deadlines are so short I've been able to change gears many times. All the while developing things that I like and things that I don't like, and locking into those for my personal work. That's not to say I hold one in higher esteem than the other. I loved my career as an illustrator, but I have experience there, and I'm looking for the new experience, the new thing. You asked me about the things that I really enjoy; I love writing, too. I've got this theory that my twenties were illustration, my thirties were painting, my forties are gonna be writing. But, we'll see if it holds true. I think those things are probably going to overlap and converge and I don't know. I'm not as rigid as I once was [laughs].

Talk about your personal voice.

I think the personal voice gets framed differently between personal work and commercial work. I feel that the majority of commercial artists are subject to the whims and the intentions of the writer, the editor, the art director, and the manuscript. That's not to say that there aren't individuals who identify themselves as individuals within the industry—obviously, we have people we hold in high regard who found a personal voice in spite of the fact that they're reacting to someone else's content in the first place.

In illustration you're given the parameters of the assignment—and I think parameters are fantastic. I really think that they're necessary to get things done. Deadlines, timeframes, proportions, content, all give you a very focused direction in which to pursue your own personal agenda. I also think that client work is a wonderful opportunity to encapsulate the client's needs within your own, and usually that model gets flipped upside down where we are subject to the client's needs and our own needs fall secondary.

All illustration programs talk about problem solving. And [problem solving is] important, a major part of the equation, but what it's saying is that there's always a problem to solve, and that someone else is giving you a problem. Well, where do those problems come from? Who initiates those in the first place? That call, or email, or job is the validation for doing the artwork. So in pursuing your own voice, you have to realize that that's half the coin. The other side of the coin is problem-framing, or problem identifying, where you actually initiate the problem yourself, and if you can do that, you go from facing a blank canvas [to] building what I call a three-sided box, and it gives you an opportunity to move very specifically and deliberately in a direction.

What do you feel you've had to sacrifice to pursue your passion (which is story)? Or even just to be an artist?

When I say story, I kind of left that hanging before: as a painter, as someone who's got ambitions to write, the focus on the narrative moves away from the external story. The story of someone else and someone else's experience, these fictional things, become a fixation on your own story. It becomes internal versus external. I think that that's where personal boundaries and goals and parameters can make you a little bit bulletproof, in the sense that you're no longer subject to critical scrutiny to the same regard. The standards just don't apply, right? "You can't draw well." Well, I didn't mean to draw well! I drew naively, on purpose. I did this because I was trying to accomplish this, I did that because I was trying to accomplish that.

As our own worst critics, we certainly can validate the things moving forward. I've had shows where people come up and say "You know, that wasn't as interesting as things I've seen you do before." I know that, but that thing [they originally liked]…never would have existed had I not gone through the process or willingness to fail, or do things I hadn't done before. That concept is really important to me, challenging those boundaries of what you know and what you don't know.

As relates back to sacrifices, things that you give up...there's a lot of people in life that you meet, and in college I had a lot of friends that were business majors, and people who were in medicine and different disciplines, and so many of them work nine to five jobs. And they might like their work—a lot of them hate their work—but they live for the weekends, and they have really strong friendships and things of that nature. I think the thing I end up sacrificing the most is relationships. And I don't mean that in the way that family is sacrificed, but it's an ongoing battle. I kind of joke around that art is my mistress, and my wife hates her, but it really is a time issue.

Being creative is Pandora's box. How do you control it, how do you live your life in a way so that it's fair to someone else you're in a relationship with? Friends, parents, your spouse, your kids. So I'm not sacrificing my immediate family, but I do miss relationships with friends, I miss recreation. If I were to list the things in my life that should take most priority, health would be number one, because if you're not healthy you can't do anything, you're no good to anybody, and that can hurt people more than anything else. So, a focus return on health would be great, and I go through periods where that is a focus, and other times, like the past month, where it's not. Health, recreation, relationships, and business, are the four categories of my life that have importance. Everything that matters to me falls into those categories, and everything else becomes secondary.

Never give your dreams and your ambitions over to another person. If you are in a business or industry where you are completely in control of the things that you're pursuing, isn't that a liberating concept? No one can ever fire me from being an artist.

It sounds like you're very motivated by setting a goal, accomplishing it, and moving forward. Where do you think that drive comes from?

Wow. Where does ambition come from? Ambition is such a two headed monster. It propels you, but it's the dragon that you're always trying to slay, too.

I would like to be able to go on vacation and relax. I would like to be able to turn off my mind and have some quiet time. It doesn't work that way. The hardest thing in my life, the most difficult thing that I struggle with is being present. Right? [Being there] with someone, and silencing everything in my head, and the stress and responsibility, pushing that aside so [I] can focus on that individual is the hardest thing in the world. I'm very aware of it, and I think I'm figuring out some devices to do that, but we live in a day and age where everything's pining for your attention anyway, and we're always on call, social media is always telling us to put our stories out there and build our legends and build a fan base, and all these things that play to our ego so much that it becomes exclusive of shared experiences with other individuals in a group.

I would say, as far as where that drive to live life comes from…that is tough. I haven't been stumped like this in a while. I know what motivates me to make art. I think a big part of that is going back into my youth. My brother and I were just kids, making things and drawing things all the time. I was in kindergarten, and our teacher asked us to make a drawing for Thanksgiving. I was sitting in my class and drew a picture of an Indian, and we put [them all up] on the wall. And this always sounds arrogant to say it, but even in kindergarten, I looked around and I knew my drawing was better than everyone else's drawing. I don't know by what context I based that off of, but I knew it. It wasn't even a question.

I had this assumption, and then the teacher brings the entire class over and starts making a big deal over my drawing. No one else's—mine! So it was assumption and validation. I use that model to this day with my work. Painting and drawing is what I do that affects other people the most. They see it, and it initiates a reaction. That has been something that's propelled me forward. I've realized "Okay, this is a thing that I have. This is how I identify myself." It will always be a part of me. I can languish on it and put it aside and let that get beaten down, or I can pursue it.

I think that's where part of [ambition] comes from…, I can very vividly, as mentioned before, imagine myself eighty- years-old, looking backwards, and that fear is so distinct and clear to me: I've got to do something. I don't know where that [urge] comes from. I think I could easily get overwhelmed by that emotion…and fall into depression, but that's another one of those things that, maybe early on, I figured out how to wrestle with and use as a positive instead of a negative.

How to run at hills.

How to run at hills. That's always been there.

How do you deal with your goals that maybe are unattainable?

I say this, and people always laugh, but in high school I was dead set on being a professional basketball player. That was my life's goal at that time. Some people would beg to differ, but I got pretty good because I worked really hard. If anyone knows the movie Hoosiers, I was Jimmy Chitwood, and I would carry the basketball with me everywhere I would go. I would practice in the morning, I would practice at lunch, I would practice at practice, and I would practice after practice. It was obsessive. I would do shooting drills at night, just sitting in bed, shooting hoops in my mind.

I had some issues with confidence in high school, many people do. It inhibited me a lot, but I continued to play in college intramurals. I could have played college basketball somewhere, maybe division III, maybe division II, I don't know. But I did realize that the things that came most naturally to me, artwork and storytelling, required a whole lot less work than what I had to go through to be a basketball player. I loved that [basketball] part of my life, and I'll never fulfill it, and I miss it, but don't get me wrong: I've failed plenty in my life. It's finding life goals, though, that are things that you can continue to pursue and better yourself at that afford you the opportunity to sustain an interest and carry on.

And maybe that's what's so interesting about art and creativity. It doesn't have set boundaries. There's no one in the world who can tell me I can't do it. I mean, I'd do it anyway. In basketball, there were limitations. At some point, someone was going to pick me up or they weren't, to play at their college or move beyond that. That decision was going to be made by someone else. As an artist, the only person who can ever tell you that you can't do it is yourself. It's got to be a very difficult place to get to; either life gets in the way, or you just stop believing and you let things distract you.

It's interesting. I get people who ask me: "Can you look at my portfolio? Do you think I have what it takes to be a professional artist?" Here this person is in a very fragile place in their life where if I say yes, maybe they continue on. If I say "No, you have no business in this industry"—which I would never do, but I'm half inclined to say to see how they respond. Because there's going to be a lot more harsh criticism that comes along than that. Never give your dreams and your ambitions over to another person. If you are in a business or industry where you are completely in control of the things that you're pursuing, isn't that a liberating concept? No one can ever fire me from being an artist.

The point of art was never art for the sake of art. It's to mirror life, to bring that emotional connection to another person. So, if you're stuck in the studio or in front of the computer toiling away all the time how can you possibly connect to other people?

If you could summarize advice in just one word, for other creatives, what would it be?

I've got a lot of advice for other creatives. Everything from trying to identify the reasons you do this in the first place, because we go through school systems here in the states and other countries, where every day you're told where to be, and you're put on someone else's schedule, and you're punished or rewarded for the things that you do and you don't do. That idea continues and perpetuates through higher education, and all of a sudden you get out of school, and for the first time in your life you're facing social withdrawal, you're facing a situation where no one is telling you what to do anymore. No one is punishing or rewarding you for the things you are or are not getting done.

I would encourage creative people to really dig deep and write the most honest and candid artist statement or mission statement or daily mantra, whatever it is, daily affirmation, that they believe in their heart and soul is true. We've got to get past this idea that art isn't necessary. I think as much as anything in the world it's necessary, as a vehicle for betterment as ourselves as individuals. It's a vehicle for personal therapy, it's a vehicle for communication, and if you look at how that applies when we connect and communicate with other people, it's a vehicle for the betterment of mankind. I know that sounds extremely lofty, but I believe that in my heart and soul. I believe I have a role to play as an artist and communicator, I have a responsibility beyond what do I want and what's in it for me. I'm just another thread in this larger tapestry. We have the ability to change thought and change direction for people.

If you can find out what your motivation is, and you really believe it, then when all those constructs of the armature of education and everything I previously mentioned fall away, and they will fall away, you'll know exactly what you have to do to validate what you're doing. I think getting down to that core concept is probably the top-down lesson that I would pass on to people. Start with that. It's like a maze working backwards, and if you know ultimately what you want—even if you don't have a clue how to get there—you're going to figure it out. Mazes are always easier to solve backwards than they are starting from the middle. And if you have that kind of perspective you're going to be presented with challenges and they can be rolled over into opportunities and you're going to be alone and distinct because your set of experiences as a person on this earth—no one's ever had those experiences and no one will ever have them again—the more you can interject that into things you do, the more genuine and honest the work is going to be.

So, in one word? [laughs]

In one word….the word is "experience": your own individual experience. Experience life, live life! Have something to tell people about. Live to tell the story has been my handle recently.

Note: Original interview content has been modified for length and focus. See full interview here.